Cyd Charisse could do it all: sing, act, and dance like music coming to life. People knew about her long legs. But the woman who looked like she was built for the spotlight was actually a frail, skinny Texas girl named Tula Ellice Finklea. After she got polio, her parents put her in ballet to “build me up.” It did more than that; it gave her a new life. When Hollywood finally called, producer Arthur Freed corrected her brother’s misspelled “Sis” to “Sid.” This is how the name Cyd, which the world remembers, came to be.

She grew up in Amarillo, where the wind and dust were more prevalent than lights on a stage. Ballet altered her body and gave her a purpose in life. She began studying with professional tutors by the time she was a teenager. At first, she did this in Los Angeles, and then she did it abroad. She mastered classical lines and épaulement, which would become her style. When she started touring with ballet, she tried out Russian-sounding stage names for a while, like many American dancers did back then. But the essence of her style never changed: a calm, unfussy grace wrapped around great musicality.

She got into movies through dance, not talking. She first shows up as a shimmer—uncredited jobs, specialty data, and that calm girl who moves differently than everyone else. MGM signed her while it was at its peak and let her grow. She looked like quicksilver next to Gene Kelly in Ziegfeld Follies (1945). The way she looked was a foreshadowing of things to come: even in a few bars of choreography, her line read throughout the room. Then came the scene that made her famous in movies: in Singin’ in the Rain (1952), she floated through the “Broadway Melody” ballet with jet-black hair, a poisonous green dress, and legs that seemed to stretch on forever. She expressed everything without saying a word. She comes and goes like a dream, but the mark stays.

People love to argue over Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly, and Charisse is one of the few dancers who made both guys look better than they really were. She could strike back with silk-covered steel against Kelly, and she could convert breath into speech against Astaire. There are absolutely no fancy dances or camera techniques in “Dancing in the Dark” from The Band Wagon (1953). It’s just two folks walking into a waltz in Central Park. But it seems like it goes on forever because of what Charisse does: the little pause before she gives in and the way her back tells you what her face won’t. Astaire is said to have dubbed her “beautiful dynamite.” She thanked him back without picking a side and said something like, “That’s like comparing apples to oranges.” The truth is that she talked to both music gods in the same way.

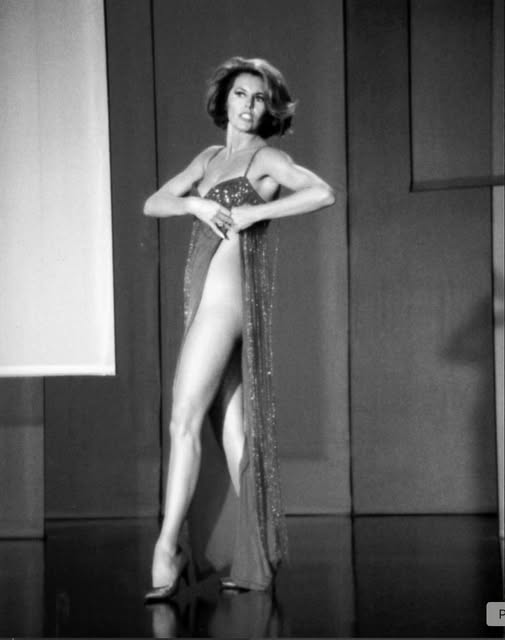

Her legs weren’t the only thing that made her stand out (publicists preferred to say that Lloyd’s of London insured them for a million dollars). It was how she talked about moving. You could stop any frame and see the ballet training: the long, straight line from shoulder to wrist, the carriage, and the turnout. She didn’t do ballet steps; she breathed through jazz and modern shapes until they felt like they had to happen. Observe how she shifts her weight, how her foot finds the floor like a cat, and how a turn concludes with the softest whisper of a head. Some dancers give you speed, but Charisse gives you time—how to stretch it, hold it, and then snap it like a silk ribbon.

Even if the music started to go off in the 1950s, MGM kept her occupied. There are so many great moments: the noir-tinted danger of her vamp in Singin’ in the Rain; the cool sophistication (and sly humor) of The Band Wagon; the tart sadness of Brigadoon (1954), where her epic line softens for a Highland romance; the urban bite of It’s Always Fair Weather (1955); the urbane fizz of Silk Stockings (1957), where she updates Garbo’s Ninotchka with deadpan wit and deadly glamour; and the smoky, grown-up appeal of Party Girl (1958), whose nightclub numbers doubled as character studies. Even though the script did, the choreographers didn’t shortchange her. They gave her room because they knew that the camera likes to watch from a distance.

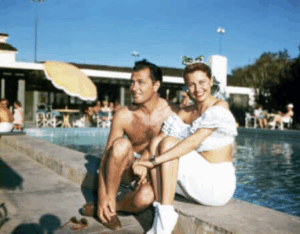

She was the studio’s fantasy off-screen: always on time, ready, and not interested in drama. When she was very young, she married Nico Charisse, who had been her dance teacher. They had a son named Nico Jr. In 1948, she married singer Tony Martin. Their second marriage lasted for 60 years, which is practically a record in Hollywood. People who worked with her said she was shy and snarky, and she would rather remain home than attend to parties. She preferred rehearsal clothes to gowns and orange juice to martinis. When the movie musical ended, she went on to TV variety shows, European movies, and finally the stage without feeling sorry for herself. She and Martin did a fancy nightclub routine. She wowed Broadway audiences in Grand Hotel in the 1990s with the kind of authority that comes from years of experience.

A life touched by stardust isn’t pain-free. American Airlines Flight 191 crashed after leaving Chicago in 1979, killing everyone on board. Sheila Charisse, who was 36 years old and married to Cyd’s son, was one of them. People still talk about the disaster in hushed tones, like it was one of those American tragedies. The incident left a hole in Charisse and her family’s life that would never be filled. It reminded me that being calm under pressure isn’t just a gimmick.

She kept working, teaching, and mentoring, though, and she warned younger dancers that looking good without being good is just wearing clothes. She won the National Medal of Arts in 2006. This was an official acknowledgment of what dancers, directors, and fans had understood for fifty years: that she helped shape an art form in movies. Two years later, when she was 86, she died of a heart attack. Tony Martin came next in 2012. Even though their extended duet was over, the music kept playing.

You should truly look at what she did three times.

“Broadway Melody” (from “Singin’ in the Rain”) — She moves like a knife that has been wrapped in satin. The famous green suit isn’t just a garment; it’s a dance. The bias cut makes every step look like a sketch, while the slit displays the engine. When she folds into Kelly’s arms, it appears like she’s giving up, but her spine never does. She can choose to be gentle.

“Dancing in the Dark” is a song on “The Band Wagon.” No fireworks. Breathing and a walk that won’t end. The way she extends her leg and lets her heel touch the ground shows what the music can’t: that love is about rhythm, not fighting.

“Silk Stockings” title number— Charisse uses silence as a weapon. The humor is serious, yet the control is strong. She shows you the army hidden in the satin and then laughs with you when you figure it out.

Her presence has a wider impact than merely the set pieces. Before Charisse, the ideal for a leading lady in a musical was “an ingenue who can move.” After Charisse, choreographers started writing for women who could dance like Astaire did—women who weren’t just pretty but also the main focus of the dance. Directors learnt to keep the camera on a shot longer, editors learned to cut less, and partners learned to pay attention. She made place for the next generation of dancers, who weren’t afraid to be statuesque, modern, or hard to work with.

The million-dollar legs, the calm hauteur, and the green outfit that made a thousand people fall in love are all popular stories. But the deeper truth is better. Cyd Charisse showed that strength can look like silk, that elegance can be athletic, and that a story can go down a calf and across an ankle to land softly, exactly on the beat.

The movies still play after a long time. Put on The Band Wagon and turn the park into a dance floor. Put on “Singin’ in the Rain” and see how the green dress transforms in your head. Watch Silk Stockings again and pay attention to how a lifted eyebrow may be a dance. You don’t have to miss her to enjoy her; you just have to see her.

Movement was her language. Her legacy is still dancing.