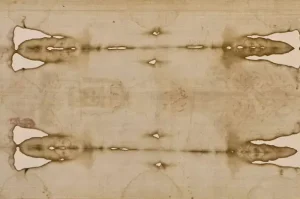

The Shroud of Turin’s legitimacy has been a topic of considerable controversy and interest among religious, historical, and scientific societies for a long time. This old piece of linen, which first showed up in historical records about 1353, has a faint picture of a man with wounds that seem a lot like the ones recounted in the Bible when Jesus Christ was crucified. There are marks on the material that seem like wounds on the wrists and feet, as well as impressions that look like a crown of thorns. Many Christians thought that the Shroud might be the fabric that covered Jesus’s body after he died because of these facts.

For hundreds of years, this notion was crucial to people’s spiritual and cultural lives. Many people thought the Shroud was a holy relic. The linen’s mystery is due to its history and the image’s strange, unexplained creation method. But new research published in the journal Archaeometry gives us new evidence that goes against the long-held belief that the Shroud touched Jesus’s body directly.

Cicero Moraes, a Brazilian 3D designer who specializes in recreating historical faces, used powerful computer modeling methods to look at the Shroud’s visage. He acted out how cloth moves as it is draped over two distinct kinds of shapes: a realistic human figure and a low-relief sculpture, which is a surface with little three-dimensional bumps like wood carvings or stone engravings. Moraes compared these digital fabric simulations to precise black-and-white photos of the Shroud obtained in 1931. He concluded that the patterns and folds on the cloth look more like how fabric would hang over a low-relief sculpture than over a full three-dimensional human body.

This finding makes it possible that the image on the Shroud wasn’t made by touching a real body but instead by employing a molded form. Moraes said in an email interview that the image on the Shroud matches what would happen if the cloth were laid over a low-relief matrix made of wood, stone, or metal. This kind of matrix may have been colored or heated where it touched the textile to make the pattern seen on the cloth.

When Moraes simulated fabric draped over a three-dimensional body, the simulated cloth changed shape and size in ways that didn’t match the image on the Shroud. When the fabric was stretched over a low-relief shape, there was no swelling or deformation. This supports the theory that the Shroud’s appearance may be an artistic production rather than a real body impression.

Moraes admits that there is a small chance that the image is an imprint of a real human body, but he stresses that it is more likely that artists or sculptors with enough skill made the Shroud to create such an effect, either by painting techniques or by using a low-relief matrix. This new information changes the conversation from solely theological speculation to art history and scientific investigation, giving us new ways to think about how the Shroud might have been made.

These latest results are in line with carbon dating tests done in the late 1980s that showed the Shroud’s fabric was made between A.D. 1260 and 1390. This timeline shows that it was made long after Jesus’ time, which supports the idea that the Shroud is not a real first-century relic but a medieval artifact. Although the precise origins of the Shroud remain enigmatic, Moraes’ discovery adds to an expanding corpus of evidence indicating that it may have been an artistic portrayal intended to evoke devotion rather than a literal burial shroud.

People are still genuinely interested in and passionate about the Shroud of Turin dispute. This is because it raises bigger questions about faith, history, and the relationship between science and belief. Moraes’ study makes us reconsider what we believe to be true and pushes us to see the Shroud as more than just a religious symbol. It is also a complicated object that was made by people and molded by history.